The secrets of forging

Mizuno's claims to be ahead of the game

Masao (55), a trained metallurgical engineer, has worked in Mizuno Golf research for 31 years and designed the world’s first mass-produced titanium driver – the Mizuno Pro ti-110. It was released in 1990 with a 200cc head. “But believe me,” he says, “It was impressive at the time.”

You can think of casting like making ice in your freezer. You are turning a liquid into a solid by using a mould. Cast irons tend to be made from a stainless steel alloy. The steel goes into a furnace, melts and is then poured into a ceramic mould. When everything has cooled down the mould is broken, leaving the club inside. With forging, the club is fashioned from one piece of metal. At Mizuno we make irons out of bars of mild carbon steel - each is 10in long and about one inch in diameter. The metal is heated until it is red hot, then hammered and crafted into shape. | |

Why does Mizuno choose to forge its premium irons, such as the MP-67 and MX-25? The forging process produces greater consistency and quality in the metal. Casting may be a more economical way to produce clubs (a cast head costs about half that of a forged head to produce). But the downside of casting is that when the metal is poured into the mould, it always traps tiny bubbles inside the metal structure. No matter how carefully you pour the water, there are always bubbles in the ice. These bubbles make the face less consisistent - two shots from almost the same place can produce very different results. If any big bubbles are trapped, this can be the origin of a crack or breakage.

Perhaps not if that’s the only club you are hitting – but if you hit one and then hit one of our forged heads, which do not have any trapped bubbles, you will instantly tell it feels more solid and sweet. | |

For the better player it is certainly obvious. We once tried to fool our in-house pro by giving him two identical-looking clubs to try. We told him both were made from forged carbon steel but one was cast stainless. The instant he hit it he turned to us and said: “What is that? It feels dead.”

The bubbles absorb the sound - and it's the same with golf clubs. Cast heads dampen the sound quickly because there is air inside the metal. That’s why they sound and feel 'dead'. Our mild carbon steel forged heads, with no bubbles, produce a longer sound duration which gives more feedback. | |

Some of the world’s most popular wedges, including Titleist Vokey and Cleveland, are cast. What do you believe are the performance benefits of Mizuno’s forged wedges? Of course for short shots you need feel and distance control – and our forging process enhances both. The mild carbon steel we use for forging is a softer metal, giving the golfer extra touch. The increased vibration we have just talked about, created by the more solid head, is again going to generate more feel, which gives the golfer greater information and feedback on the shot. But also the purity and integrity of the metal produced by forging allows the player to strike the ball consistent distances, which boosts their confidence. | |

With casting it is not easy to make a perfect, flat clubface. Again, we can compare it to ice. Look at the top of an ice cube and the top will be concave. When you make solids from liquids there is always shrinkage. It’s the same with irons. When the metal cools down there is a deformation or warping of the product, which affects the flatness of the face.

Because the golf clubhead is of uneven thickness. The sole is thicker, the top edge thinner. This causes different parts of the club to cool at different rates – the sole cools down slowly, while the top edge cools down quickly. There will be a stage when the top of the club is basically solid, while the bottom is still softer. It creates a pulling or a stress inside of the club, which promotes the warping.

Molten stainless steel is more liquid, so you can avoid bumps or not filling a recess. But also 17-4 stainless steel, the most famous one, is very strong, twice as strong as mild carbon steel that is used for forged heads. The strength is good for design flexibility – you can make thinner walls in cavity backs for example – but its hardness means it cannot be forged so well. The material tends to cracks or break when it's hammered. | |

It gives the perfect blend of hardness and feel. The ‘1025’ means there is 0.25% carbon in the steel. The carbon content affects the hardness of the metal. If you go to more than one per-cent it gets hard but also brittle. If you go lower than 0.1 per-cent the metal is too soft - it can deform while you play. We wanted a substance that was resilient but had feel, and which was malleable enough to stand loft and lie adjustment. The 1025 steel was perfect.

The 1025E Pure Select is a purer metal which will give even greater consistency. We believed the original 1025 steel was a wonderful metal for a golf club but our quest for perfection led us to look for ways to improve it by reducing unnecessary elements that occur during forging – specifically phosphorous and sulphur. On rare occasions, these can slightly affect hardness in the face. Now we’ve found a way to do that. The new metal is also better at minimising so-called 'craftsman’s marks' that can be caused by bending the hosel for loft and lie alterations.

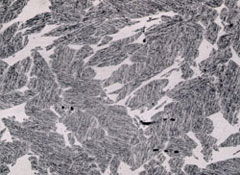

I mentioned that our irons are forged out of metal bars which have a natural flow of the fibre - a grain. This grain acts as a strengthener/reinforcer, improving the block’s integrity, consistency and durability. Think of it like concrete, reinforced by steel rods inside. The grain acts like the steel rods. Mizuno is the only company to arrange and control this flow to pass on a performance benefit to the golfer. We do our best to maintain this flow into the finished head. It makes the club stronger and more consistent. We achieve it by taking the bar and stretching about half of it into a narrower diameter. This end eventually becomes the hosel but because it is a squeezing, stretching action, we maintain the flow of the grain that is trapped inside the bar. After this we put the half with the squeezed metal into the primary forging mould and then we forge it, so this hosel portion becomes the hosel and the other part becomes the face. We have minimal waste. Other companies don’t do this They tend not to care about the metal’s grain and rather than stretch the rod they pound it and hammer it. creating a lots of flash – (unnecessary parts) which must then be taken out. Usually that's done by milling and grinding which cuts through the natural flow of the fibre and can make irons weaker and less consistent. | |

It combines material consistency and strength with a very satisfying solid feel. Our competitors haven’t the same experience in the forging of golf equipment. They’ve been forced to supply forged equipment as their Tour professionals will rarely accept a cast head. The forging houses they use have tended to resort to forging their irons from two separate parts – a steel face welded to a steel hosel. Since our competitors are re-introducing forged irons we have started buying their clubs to cut apart and check. We usually find the face and hosel have been welded together, which can break the flow lines of the metal and create an inconsistency in structure from iron to iron. Although forged they cannot compete with Mizuno’s Grain Flow Forgings on feel and consistency.

For one thing our clubs are forged in the exceptional Chuo forging house with whom Mizuno has exclusively worked with for 38 years. We are always trying to improve and our new 1025E Pure Select steel reflects this. Today we believe we are the champions in the forging industry, but even now we put lots of resource – plenty engineers and lots of hours – to improve our process. That’s our general direction and we believe that in the field of business, quality is the key thing. We do not want our competitors to catch up with us. Tell us on the forum your experiences of forging and cast heads. Has this feature helped you understand the processes? What differences in performance have you discovered? |